Click to expand Image

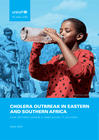

Protesters hold banners and chant slogans during Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s official visit to Germany on July 18, 2022, in Berlin.

© 2022 Omer Messinger/Getty Images

Earlier this month, Human Rights Watch released a report exposing how Egyptian authorities are refusing to provide identity documents including passports, birth certificates, and national IDs to critics living abroad. The goal appears to be to disrupt their lives so much that they have to choose between effectively becoming undocumented or returning to Egypt, where they could face jail time, even torture.

Following the report, Egyptian critics living in the United Kingdom and Qatar have approached me to say they have suffered similar abuses.

One of the pernicious details we uncovered in our report is how some foreign missions, including the Egyptian Consulate in Istanbul, require citizens accessing services to provide extensive, unnecessary details such as their reason for leaving Egypt and links to social to their media accounts. The forms are then sent directly to security agencies in Egypt who approve or deny access to these services.

Critics living in Qatar say a similar process was introduced by the Egyptian Embassy there several months ago. Under the new system, people applying for passports must now fill out “security clearance” forms, not stipulated by laws, which must be approved by security agencies in Cairo before a passport application can be made. The “results” are published on the embassy’s Facebook page. The same process applies to infants and children.

One prominent human rights defender who applied to renew his national ID in Qatar waited six months to find out whether he had been successful. When his result was finally published on the Facebook page, next to his name was a single sentence: “the citizen must come [to Egypt].” A lawyer, acting on his behalf, visited the Civil Registry in Cairo but was told that security agencies “blocked” the ID renewal.

The effort to punish dissidents abroad stands in stark contrast to President al-Sisi’s April 2022 call for political dialogue “with all [political] forces without exclusion or discrimination.” Almost a year later, the dialogue has proven to be little more than a public relations stunt to mask ongoing mass repression.

If President al-Sisi is serious about the inclusivity of this dialogue, he should show good faith by instructing his authorities to halt the targeting of critics abroad and by releasing the thousands of people who are unjustly detained. If he can do this, people may feel safe enough to return and to take part in genuine dialogue that isn’t state-managed, talking to each other in the streets, cafes, the markets, schools, universities, and in the media.